Unpacking Some Loaded Claims about Beef Industry Concentration

Temporary disruptions to the beef supply chain during the COVID19 pandemic have generated an enormous amount of attention for the beef packing sector, including the resurfacing of many false and misleading claims about the industry’s structure and how it operates.

This summary details the real facts behind the beef packing sector, setting the record straight by correcting the false claims, clarifying some misunderstandings they’ve created, and putting the structure of the beef packing industry into proper context.

The fact remains, the U.S. meat packing sector is a dynamic, resilient, and highly competitive industry with a long history of providing an abundant supply of high quality, safe, and affordable products to American consumers and serving as a vital economic engine that supports America’s farmers and ranchers.

Industry Concentration and the Supply of Beef

It is often repeated that virtually all the U.S. beef supply is uniquely in the hands of just a few companies; this claim is greatly exaggerated.

The top four beef packers in the U.S. account for the purchase and slaughter of about 84 percent of all fed cattle in the U.S., according to the most recent report from the USDA’s Packer and Stockyards Division. But those fed cattle make up about 79 percent of the Federally Inspected cattle slaughter in the U.S. The other 21 percent is made up of cows, both dairy and beef, and some bulls.

Thus, the “Big 4” beef packers, even factoring in the cow slaughter plants they own comprise closer to 65 to 67 percent of U.S. beef production.

What’s the difference? Fed cattle are steers and heifers that packers purchase from feedlots after being brought to market weight on a diet of grain to produce boxed beef, i.e. primarily the muscle cuts that consumers demand as steaks, ribs, and roasts. Cows and other non-fed cattle, on the other hand, are primarily slaughtered to be made into hamburger. The lean meat from these animals is a necessary ingredient to be made into America’s supply of hamburger produced in combination with the less demanded muscle cuts from the fed cattle.

Why is that important? About 50 percent of all beef in the U.S. is consumed as hamburger.

Indeed, the beef packing industry is like many other mature, capital intensive industries that operate on a large scale – from airlines to cellular phones and internet providers, to automotive and home appliance manufacturers – whereby the production of several bigger companies is complemented by a much larger number of medium and small enterprises. The hundreds of companies that make up the North American Meat Institute reflect the breadth of the meat industry’s make-up and include companies of all sizes and structures including single plant companies, producer-owned, family-owned, and corporate operations.

Market Power in the Industry is Not Consolidating

Much of the rhetoric about industry concentration implies that consolidation in the beef packing sector is ongoing and that market power is becoming more and more concentrated. That certainly is not the case.

The 1980s and early 1990s were a period of industry mergers and acquisitions. As USDA’s Economic Research Service noted then:

Many economic forces underlie decisions to shut down plants and purchase others, most importantly, changes in demand and technology. For example, technological change has led to larger beef packing plants. At the same time, declining beef consumption has lowered production across the industry.

In short, industry consolidation was a factor – not a cause – of broader market forces.

Importantly, this restructuring activity was carefully reviewed contemporanesouly by the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice (DOJ), in coordination with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and USDA’s Packers and Stockyards Division (PSD), during Administrations of both parties. Further, none of these enforcement and oversight agencies, who monitor the sector regularly under Administrations of both parties, have found cause to pursue any actions or remedies.

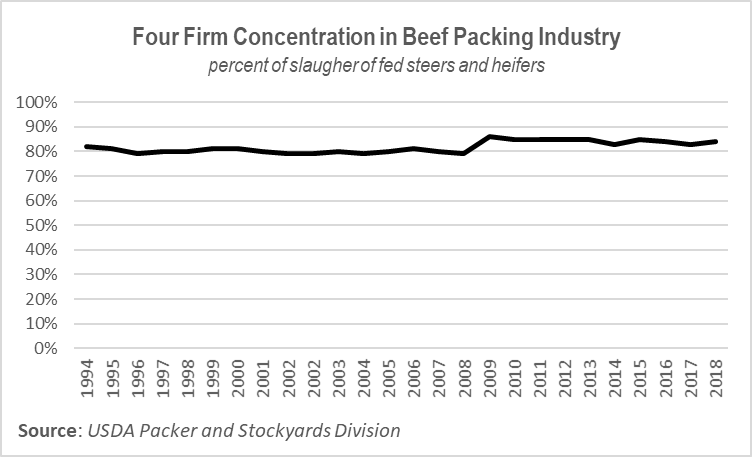

In the fed cattle industry, the four-firm concentration ratio has not changed appreciably over the past 25 years. According to USDA, in 1994, for example, that ratio was 82 percent, compared to about 84 percent today.

The four-firm concentration ratio is monitored closely by PSD, an agency uniquely charged, by statute, to provide on-going oversight for fair business practices and to ensure competitive markets in the livestock, meat and poultry industries.

While there have been several ownership and asset transactions in the industry over the past two decades, as the chart shows, those transactions have not resulted in greater packer concentration. Newly structured firms within the industry should not be confused with consolidation of existing industry players.

And as stated above, proposed mergers and acquisitions that have the potential to increase industry consolidation – and reduce competitive market forces – must pass strict scrutiny by the DOJ and FTC. For example in 2008, after a thorough review, DOJ blocked the last proposed major acquistion based, not on the size of the post-merger company, but rather on concerns about the location of certain plants involved in the deal and the potential adverse impacts that might have on competition in the regional fed cattle market. In short, there are oversight checks on the industry to protect the market.

Plant Size and Capacity Reflect Market Factors, Not Concentration

Often industry critics mistake individual packing plant size and slaughter capacity with overall industry concentration. This has especially been the case during the COVID related disruptions. However, the size, location, and number of plants reflect basic economic factors like the cattle supply and the economies of scale in the beef business. Those economic forces exist whether the ownership of various plants is broken up.

First, the cattle supply itself is concentrated. The farms and ranches that produce about half of all beef cattle in the U.S. are in just 7 states. Further, more than 70 percent of all fed cattle are in just 5 states - and 55 percent of the U.S. corn crop that supplies those feedlots is grown in just 4 Corn Belt states. That supply dictates where fed cattle slaughter plants are located. Likewise, cow slaughter plants rely on a supply of cull cows from pasture-based smaller cow-calf farms or dairy farms and are structured based on those factors.

Second, each plant has its own cost structure. Packers bid on cattle based on the supply and demand factors in their own region. Owning a plant in Texas does not change the bottom-line to a company’s operation in Iowa or Colorado.

Third, the economies of scale drive the capacity and production of a given packing plant. That is especially true in areas with large numbers of fed cattle. Like all industries, beef packers work toward optimal efficiency – which reduces operational variable costs and fixed overhead costs – while striving to improve quality and meet consumer demands. Minimizing the costs in the middle of the value chain has proven benefits to both ends, including better returns to cattle producers and feeders and lower costs to beef consumers.

# # #

Summary Talking Points

- The top 4 beef packing firms do NOT control 85 percent of the beef supply – they purchase and process 84 percent of the fed cattle in the country, which is about 65-67 percent of the total beef supply.

- About half of all beef demand in the U.S. is for hamburger.

- The 4-firm concentration ratio in the beef packing industry has not significantly changed in the past 25 years. It was 82 percent in 1994 and is 84 percent today.

- Size and capacity are factors of a particular plant’s bottom line; reducing concentration will not shrink plant size.

- Beef plant locations largely reflect the supply of cattle – reducing concentration will not increase the cattle herd in another part of the country.

- Efficiency in production that comes from economies of scale benefit both cattle producers and beef consumers.

- U.S. meat packing sector is a dynamic, resilient, and highly competitive industry.

- The beef industry has a long history of providing an abundant supply of high quality, safe, and affordable products to American consumers and serving as a vital economic engine that supports America’s farmers and ranchers.