Putting Beef and Pork Exports in Context

Exports Benefit the Domestic Supply of Beef and Pork

Exports support expanded U.S. production of beef and pork. According to the U.S. Meat Export Federation (USMEF), in the first quarter of 2020, about 12 percent of total U.S. beef production, and 28 percent of pork production was exported. Export demand contributes to farm and ranch profitability and helps maintain the nearly 800,000 jobs in the meat packing and processing industry. Moreover, domestic consumers benefit directly from the unique dynamics of the export market, which helps balance the supply and demand for meat found on retail shelves and restaurant tables.

For example, there are only so many cuts, from pork bellies to chops, or from prime rib to tenderloins, that can be processed from one animal. For many of these items, demand would outpace supply were greater overall meat production not supported through exports. The market works because many of the cuts undervalued in the U.S. earn a premium in the export market. Therefore, a strong export market for these items helps maintain a greater supply of chops, steaks, and hamburger that Americans enjoy.

Without exports, beef and pork production would not only contract, but the less demanded export items would have to be absorbed in the domestic market despite consumer preferences to the contrary. Because of contracting meat production, and a change in the mix of meat cuts and items sold domestically, the volume of U.S. consumer favored items would quickly drop not only in absolute terms but also as percent of the total domestic supply of meat. Inevitably, that would lead to higher prices for those items at the grocery store and on the restaurant menu.

Exports During COVID

Recently there has been much discussion about meat export shipments during the COVID disruption and the concerns about the U.S. beef and pork supply chain. Some context is helpful.

First, this situation is unprecedented. Simultaneously, there were significant interruptions to slaughter and processing capacity and there also were unprecedented, significant disruptions on the demand side to which meat production had to adjust. Food service demand, which represents about 55 percent of overall consumer food spending in the U.S. and about 50 percent of red meat demand, was severely curtailed with the closure of restaurants, cafeterias, sports arenas, and other entertainment venues due to social distancing and shelter-in-place orders.

Food service drives the demand for several beef and pork products and many processing facilities dedicated a significant amount of their production to supplying these demands, not only in the type of products, but also in the way they are processed, packaged and delivered. For example, approximately 65 percent of bacon is sold through food service, but typically is sliced and packaged differently than how sold at retail. Ground beef for retail sale is typically leaner than the ground beef sold through food service, and there are further processing issues involved between producing for a consumer package destined for a grocery store shelf and an institutional sized box going to restaurants.

It was no simple task to convert the production and logistics of food service items to retail oriented products in such short order, especially with the unmatched spike in consumer purchases for freezer and pantry stocking. Nonetheless, the meat industry remained responsive and remarkably resilient with relatively little disruption given the circumstances.

Like the domestic food service – and retail – markets, there is significant processing capacity dedicated to the export market – again, regarding the items as explained above, but also for packaging, processing, and logistics. While many have pointed out the volume of pork and beef export shipments in April, a few key points are instructive.

First, many of the export loads shipped during this time were already destined for the export market and had been booked, sold, and in some cases processed before the idling of packing plants.

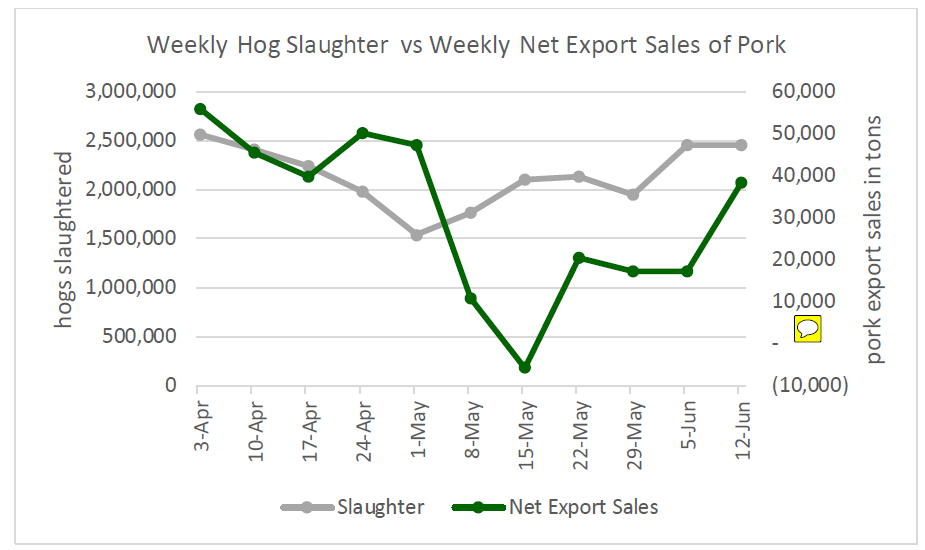

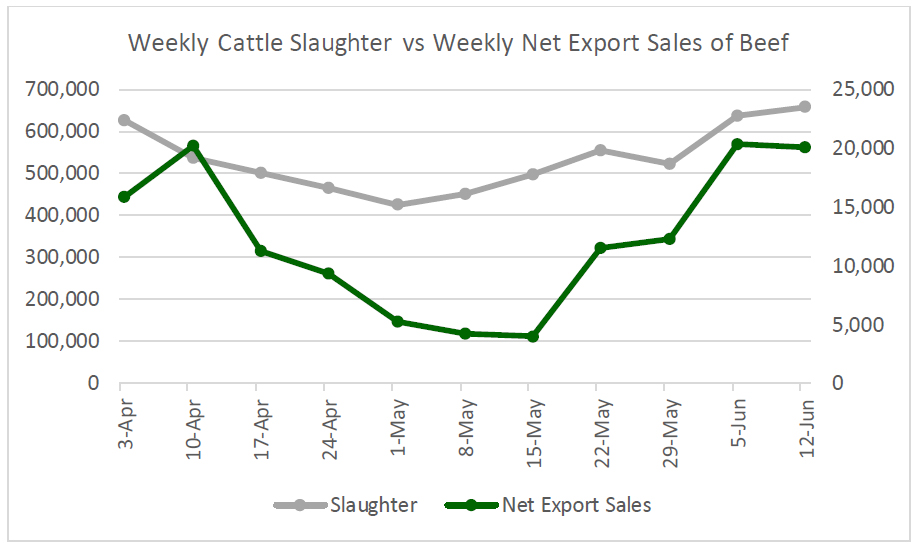

A better measure of how the sector responded can be seen from looking at the USDA data on net export sales. As Dr. Jayson Lusk, head of the Agricultural Economics Department at Purdue University noted in a recent post on his blog,

Finally, when discussing trade, I think it is really important to get the timing and trends right. If we want to explore how trade patterns responded to the plant shutdowns and reductions in domestic supplies, we need to look at data in late April and May. … it was really only in mid-April that we started seeing very significant reductions in processing volumes, with the “bottom” occurring in early May.

He further points out the

… sharp drop in sales of beef and pork at the time we starting seeing the worst of the packing plant shutdowns and closures. Actual exports (i.e., movement of meat across the border) also fell, albeit at a slower rate than sales, revealing the lagged nature between when a “sale” is made and when the meat leaves the country. It’s one of the reasons the data showed exports persisting for a few weeks even after plants began to close: the meat had already been sold weeks prior to the plant shutdowns occurring.

According to USDA’s weekly data on net export sales, new export orders dropped with the disruption experienced by pork and beef packing plants as shown in the charts below. In short, export marketing was not a threat to domestic meat supplies. Note for the chart below, an export sale is the initial booking of a new order for shipment, and the net export sale data reported by USDA shows total sales with any cancellations netted out.

Source: USDA data, NAMI

Source: USDA data, NAMI

Another important insight into the export volumes shipped in April, as reported by USDA in its monthly Livestock and Meat International Trade Data update is the mix of products, which are items not in high demand in the U.S. For example, “variety meat” exports include such things as organ meats (beef liver) and specialty items (beef tongues). According to monthly data from USMEF, nearly one in every four pounds (23.4 percent) of beef exports in April were these types of products.

For pork, variety meats represented 16 percent of total export shipments in April, but for the large volumes of export shipments destined for China and Hong Kong receiving so much attention, variety meats made up 26 percent of the product mix. Furthermore, there were large shipments of whole and half carcasses, and bone-in hams. This helps relieve some bottlenecks at U.S. packing plants as labor shortages, and new COVID related plant operational layouts and spacing affected the efficiency which large volumes of carcasses can be processed into individual meat cuts. With more than a quarter of the total volume of U.S. pork exported, having an outlet for carcasses and primal cuts that need not be fabricated into retail cuts helps support the market for farmers’ hogs and allowed packers and the hog market to recover quicker than would otherwise be the case and facilitates the production on pork cuts to supply the domestic market.

As USMEF has reported of the pork muscle cut exports this year,

Boxed carcasses accounted for 41% of U.S. export volume for China, with bone-in hams accounting for 10%. So less labor-intensive products made up more than half of this year’s shipments to China, which is critical for processors during these challenging times (emphasis added).

Supplies of Meat

Going into April 2020, meat supplies – for both the domestic and export markets – were well positioned. Even with the COVID related disruptions, total red meat production was up two percent for January through April 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. Beef was up one percent and pork was up four percent. Domestic pork supplies per capita in Q1 2020 were up about four percent from 2019, despite large volumes of exports in 2020.

As of April 1, pork supplies in cold storage were 621.93 million pounds, two percent more than at the same point in 2019. Beef in cold storage in the U.S. as of April 2020 totaled 502.4 million pounds, 11 percent more than in 2019.

Conclusion

The COVID situation resulted in unprecedented disruptions to meat packing plants, temporary production shortfalls, and near term challenges in distribution and logistics, but the supply of meat available to American families remained robust, despite temporary shifts that reduced the variety of products on some store shelves. But the U.S. meat and livestock sector remained resilient. Exports were a catalyst to getting things back to normal quickly. Export sales of pork and beef did not cause a reduction in meat available to domestic consumers. Rather, the meat industry’s ability to balance supply and demand and maintain inventories of the products U.S. consumers want through a combination of supplying both the domestic and export markets will be critical for American farmers and ranchers and U.S. consumers as economic recovery unfolds moving forward.